Hydration and Diet

A total diet approach to healthy hydration

Optimal physical and cognitive performance depends on us maintaining healthy hydration levels. This is why hydration is of interest to individuals as well as to public health experts1. Achieving water balance – when water intake matches water losses – depends on dietary and lifestyle choices providing enough fluid to meet our requirements2. However, these will fluctuate according to a variety of physiological and environmental factors which are discussed below.

Thirst is a useful indicator of daily fluid requirements but can’t be relied upon fully as the body is already mildly dehydrated by the time the thirst signal becomes noticeable3. This means that conscious and informed actions are needed to make sure that our daily life provides enough opportunities to consume fluid. This will include understanding roughly how much water is needed, checking on water losses, recognizing different sources of fluid in the diet, and making informed choices about foods and drinks.

Sources of water loss include:

- Urine.

- Faeces.

- Sweat.

- Breathing.

These losses vary enormously between people and depend on health status, physical activity levels and environmental conditions (i.e. heat, humidity). In particular, urination and/or defecation may be greater in some diseases, while sweating may be higher in a physically active person or in hot climates. An awareness of these factors is important if excessive water losses are to be rebalanced with an increased fluid intake from various sources.

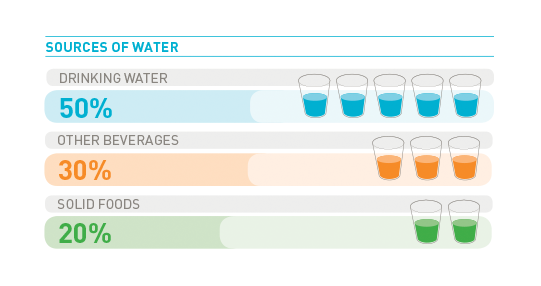

Water intake comes from many sources. Approximately 20-30% comes from solid foods and 70-80% from beverages and drinking water2.

Our fluid intakes are made up of 20-30% from foods and 70-80% from beverages

Interpreting Adequate Intakes

It is a common misconception that the recommended ‘Adequate Intake’ of water for an adult man (2.5 L/day) or woman (2.0 L/day) refers only to drinking water. In fact, the daily advice to drink 8 to 10 glasses of fluid includes beverages and food moisture as well as water2. So the official recommendations treat water as a dietary component present in all foods and beverages rather than as a single source, for example tap or bottled water.

Beverages remain the most important source of fluid in the diet. While some people can get all they need from drinking water, this is not true for everyone, particularly if water is not preferred. Thus, a wide availability of beverages increases our chances of reaching the optimal water intake. Research2 shows that the average person’s daily fluid intake is made up of:

Other beverages include coffee, tea, soft drinks, milk, and fruit juices. Caffeinated beverages are thought to have transient diuretic effects but this is unlikely to have an impact on hydration in practical terms as they also contain water and, thus, make a contribution to total fluid intakes4. Alcoholic beverages do have a diuretic effect in practice and may have a detrimental impact on hydration depending on the amounts consumed.

All solid foods contain water. For example, the water content of most fruits and vegetables generally exceeds 85%, while rice and pasta contains around 70% water. Even dry foods, such as crackers, may contain 5% water. Water-based foods, such as soups, sauces, ice cream, and custards contribute significantly to water intake.

Who is at risk from low fluid intakes?

Different life stages, certain diseases, participation in sport, pregnancy and lactation can all impact on hydration needs. Thus, it’s important to tailor eating and drinking habits to address the particular water and nutrient needs during these times.

- During pregnancy and lactation, fluid requirements are increased and women are encouraged to drink more to help prevent constipation. The EFSA Dietary Reference Values recommend an extra 300ml per day during pregnancy and an extra 700ml during lactation2;

- Certain diseases increase water requirements, e.g. fever, diarrhea, vomiting, kidney stones;

- Other diseases may require lower fluid requirements, e.g. chronic kidney disease, edema;

- Athletes and fitness enthusiasts have higher fluid needs due to greater water losses from breathing and sweating during exercise – which can be as high as 8L per day. These individuals also need to replace lost electrolytes (salts) to avoid disturbances in blood electrolyte levels2, although this is not recommended for everyone because excessive salt intake increases blood pressure5;

- Individuals living in hot climates also have higher water requirements as a consequence of water losses due to extra sweating.

These points reflect physiological changes in water requirements. For other groups of people, age, mental state or physical dependence make them vulnerable to dehydration as well as to nutrient deficiencies. Those at risk include:

- Elderly – who may have a depressed thirst mechanism or be anxious about drinking due to continence issues.

- Infants, children and disabled people – who tend to rely on their caregivers to provide the right amounts of food and drink and who may not be able to communicate their needs effectively.

It is important that caregivers are attentive to the needs of these individuals and take appropriate actions to ensure that they receive adequate food and drink.

Healthy choices for hydration

Water intake depends on eating and drinking habits as well as day-to-day variations in dietary choices. These are influenced by:

- Time of day

- Taste preferences.

- Weight management concerns.

- Availability of foods and drinks.

- Convenience.

- Attitudes towards foods or ingredients.

- Cultural differences.

- Seasonality.

- Perceptions about product quality and safety.

Dietary guidelines for healthy eating and drinking are an important consideration when making choices about foods and beverages to include in the diet. The “total diet” approach to healthy eating6 suggests that all foods and beverages have a place within a balanced diet. The key factors are consuming foods/drinks in moderation, choosing appropriate portion sizes and balancing energy intake with energy expenditure through physical activity.

Clearly, this does not legitimize unlimited consumption of foods and beverages with low nutrient density but suggests that it is overly simplistic to endorse “good foods and drinks” and condemn “bad foods and drinks”. Some beverages, particularly sugar sweetened drinks, have been viewed as significant contributors to energy intake6. However, in moderation, they do have a role in the diet for reasons of enjoyment, as well as contributing to optimal hydration.

In most cases, there are healthier choices within a food or beverage group7. This may be represented by foods or drinks with a higher content of nutrients, such as minerals or proteins, or beneficial non-nutrients e.g. polyphenols or anthocyanines. For other people, the emphasis may be on products with a low content of energy or providing lower levels of nutrients associated with chronic disease risks (e.g. saturated fat or alcohol). Thus, when choosing a suitable beverage to quench thirst and promote optimal hydration, package labels, websites and leaflets provide useful information about energy (calories), nutrients and other ingredients which help us to make the right choices for our own needs.

We would like to thanks Professor Maria Kapsokefalou for providing the content used as a basis for the text in this section.

Click here for her full scientific article entitled Hydration and diet.

1.EFSA, Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to water and maintenance of normal physical and cognitive functions (ID 1102, 1209, 1294, 1331), maintenance of normal thermoregulation (ID 1208) and “basic requirement of all living things” (ID 1207) pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/20061; EFSA Journal; 2011; 9; 2075-2091.

2.EFSA, Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for water. EFSA Journal 2010; 8:1459.

3.Kolasa, K.M., Lackey, C.J. & Grandjean, A.C. Hydration and Health promotion. Nutrition Today. 2009; 44: 190-201.

4.Institute of Medicine (U.S.) Panel on Dietary Reference Intakes for Electrolytes and Water (2005) Dietary reference intakes for water, potassium, sodium, chloride, and sulfate / Panel on Dietary Reference Intakes for Electrolytes and Water, Standing Committee on the Scientific. Evaluation of Dietary Reference